Bibliography: Gehl Jan and Svarre Birgitte. How to Study Public Life. 1st ed. 2013. Washington, DC: Island Press/Center for Resource Economics, 2013. https://doi.org/10.5822/978-1-61091-525-0.

Authors abstract

abstract:: by Jan Gehl, Birgitte Svarre., English, Translation of the author’s Bylivsstudier, originally published in Danish., How do we accommodate a growing urban population in a way that is sustainable, equitable, and inviting? This question is becoming increasingly urgent to answer as we face diminishing fossil-fuel resources and the effects of a changing climate while global cities continue to compete to be the most vibrant centers of culture, knowledge, and finance. Jan Gehl has been examining this question since the 1960s, when few urban designers or planners were thinking about designing cities for people. But given the unpredictable, complex and ephemeral nature of life in cities, how can we best design public infrastructure—vital to cities for getting from place to place, or staying in place—for human use? Studying city life and understanding the factors that encourage or discourage use is the key to designing inviting public space. In How to Study Public Life Jan Gehl and Birgitte Svarre draw from their combined experience of over 50 years to provide a history of public-life study as well as methods and tools necessary to recapture city life as an important planning dimension. This type of systematic study began in earnest in the 1960s, when several researchers and journalists on different continents criticized urban planning for having forgotten life in the city. City life studies provide knowledge about human behavior in the built environment in an attempt to put it on an equal footing with knowledge about urban elements such as buildings and transport systems. Studies can be used as input in the decision-making process, as part of overall planning, or in designing individual projects such as streets, squares or parks. The original goal is still the goal today: to recapture city life as an important planning dimension. Anyone interested in improving city life will find inspiration, tools, and examples in this invaluable guide.

This text is a classic when it comes to describing methods for counting and mapping urban life. Gehl is an architect driven by the idea

“Good architecture ensures good interaction between public space and public life. But while architects and urban planners have been dealing with space, the other side of the coin – life – has often been forgotten.” “Public space is understood as streets, alleys, buildings, squares, bollards: everything that can be considered part of the built environment.” “Public life should also be understood in the broadest sense as everything that takes place between buildings, to and from school, on balconies, seated, standing, walking, biking, etc” - Gehl Jan, 2013

Gehl emphasises that “Anyone who decides to observe life in the city will quickly realise that you have to be systematic in order to get useful knowledge from the complex confusion of life in public space.” This leads to a toolbox of some “standardised ” methods for observing public life

Gehl operates in a space between objective counting and classical passive participant observation.

He identifies three roles that the observer can assume:

- The role of registrar: for example, counting units, where precision is the most important function.

- The role of assessment: categorising people by age group, for example. Here the ability to evaluate is the most important function.

- The analytical role: keeping a detailed diary with a feeling for nuance, a trained eye and experienced sense of what type of information is relevant.

Which role the observer assumes depends to some degree on the tool being used. Here, Gehl presents eight key tools:

- Counting Counting is a widely used tool in public life studies. In principle, everything can be counted, which provides numbers for making comparisons before and after, between different geographic areas or over time.

- Mapping Activities, people, places for staying and much more can be plotted in, that is, drawn as symbols on a plan of an area being studied to mark the number and type of activities and where they take place. This is also called behavioral mapping.

- Tracing. People’s movements inside or crossing a limited space can be drawn as lines of movement on a plan of the area being studied.

- Tracking. In order to observe people’s movements over a large area or for a longer time, observers can discreetly follow people without their knowing it or follow someone who knows and agrees to be followed and observed. This is also called shadowing.

- Looking for traces. Human activity often leaves traces such as litter in the streets, dirt patches on grass etc., which gives the observer information about the city life. These traces can be registered through counting, photograping or mapping.

- Photographing. Photographing is an essential part of public life studies to document situations where urban life and form either interact or fail to interact after initiatives have been taken.

- Keeping a diary. Keeping a diary can register details and nuances about the interaction between public life and space, noting observations that can later be categorised and/or quantified.

- Test walks. Taking a walk while observing the surrounding life can be more or less systematic, but the aim is that the observer has a chance to notice problems and potentials for city life on a given route.

Each of these tools is discussed in the linked notes. Together, these tools should be able to answer Gehl’s five key questions :

- How Many? “Making a qualitative assessment by counting how many people do something makes it possible to measure what might otherwise seem ephemeral: city life.”

- Who? While registration can be done on the individual level, it is often more meaningful to investigate more general categories such as gender or age.

- Where? Studies of movement and staying can help uncover barriers and pinpoint where pedestrian paths and places to stay can be laid out.

- How long?

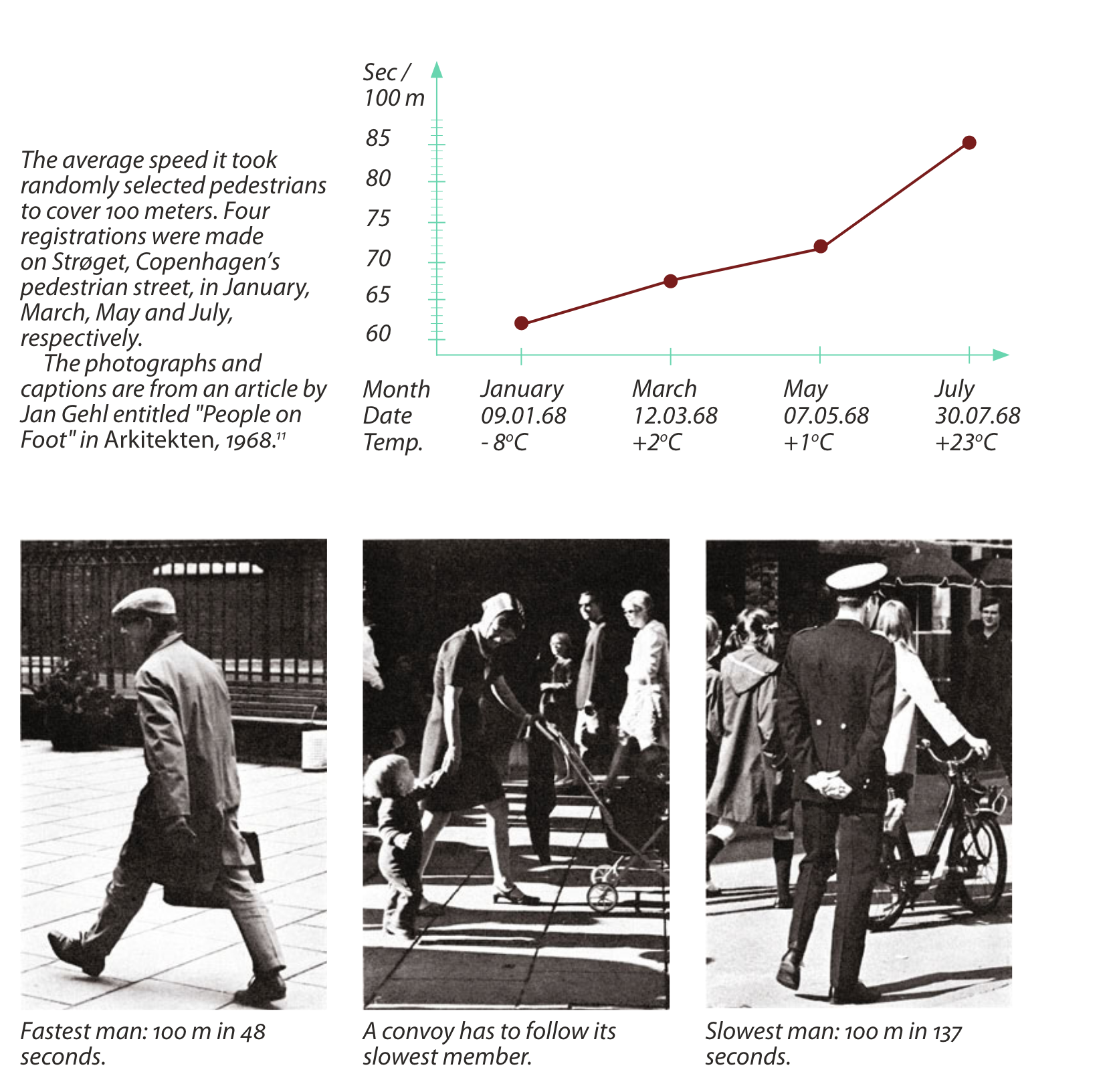

Walking speed and the amount of time spent staying can provide information about the quality of physical frameworks.